A Provocation

In the Scientific American article How Accurate Are Memories of 9/11? psychologist Elizabeth A. Phelps talked about her research where they interviewed 3000 subjects about their memories and emotions following the 9/11 attacks in the United States. The subjects were interviewed one week, one year and three years after the event. The research found that between the first and second interview the consistency was 63 percent. Even worse, the recall of emotions on that day was only 40 percent consistent after one year despite, on average, the subjects having very high confidence in those memories. Even when confronted with the evidence of their earlier surveys, subjects were reluctant to believe that the current memories were erroneous.

Yet, we rely on our memories to explain ourselves to ourselves and others. If we are to write about our lived experiences in creative non-fiction, we must use them to build our stories. What tremulous foundations! Memories are not a recording of fact, but the story you tell yourself about the last time you remembered that memory, which is being remembered by a different you in time, space and experience.

The odds are that if you are writing creative non-fiction anywhere south of the historian’s1 rigor, principles and research assistants, you are a creator of fiction. Welcome to the team, fellow fabulist! As soon as you take one fact and place it beside another, you are creating story. With selection comes omission. With each detail and additional fact, the narrative bends away from that oxymoron ‘objective truth’.

Does that bother you? Does that mean that creative non-fiction is just fiction with extra steps? Is it the intention, rather than the success, at representing truths that is the distinguishing characteristic? Should we stop with the hand-wringing and embrace, like the novelist, whatever ecstatic truths we conjure through our fabrications and delusions?

An exercise

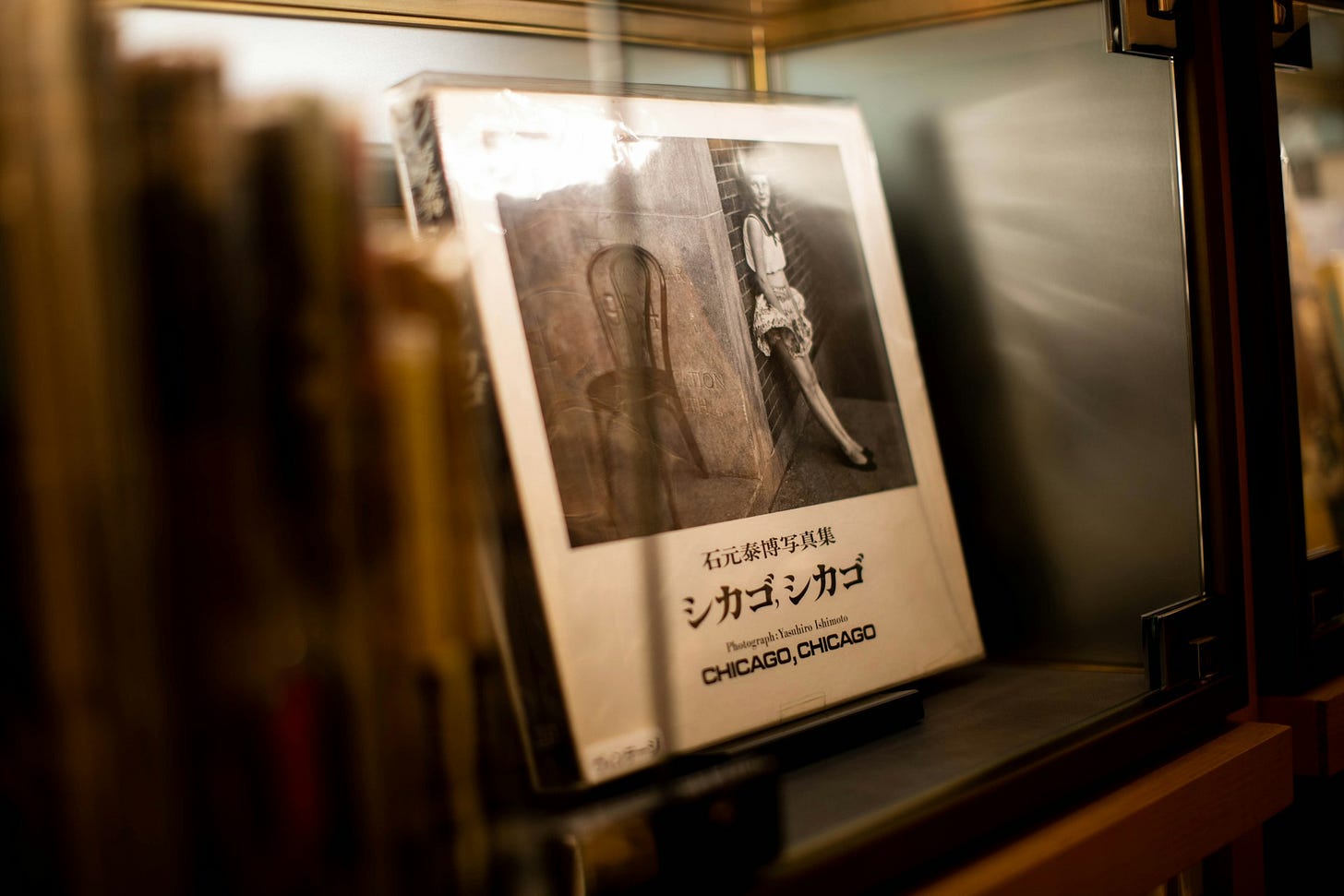

Write a memory that you couldn’t possibly have. Think about the stories that people have told you about you. Maybe during your childhood. Think about stories that actually come from photographs rather than an actual memory you have. Write about something that happened in your family before you were born. We all have these false memories, these stories. That we retain them is the important thing. What are they saying about us or what do we want them to say about us?

Jarred McGinnis was chosen by The Guardian as one of the UK’s ten best emerging writers. His debut novel The Coward was selected for BBC 2’s Between the Covers, BBC Radio 2’s Book Club and listed for the Barbellion Prize. The French edition won the First Novel Prize and was selected for the prestigious Femina prize. His current project Mountain Weight won the 2023 The Eccles Centre & Hay Festival Writer’s Award.

Hell, when historians realised that they were making it all up, they had to invent the field of historiography.

I've been remembering my great aunts and uncle recently. I remember certain things but what I realise is how little I know of their lives, and this leads inevitably to how I wish I had asked why they were vegetarians, why my uncle was a conscientious objector, why they lived in a Quaker village... If I turn their lives into fiction then I can make it up...

Memories play strange narrative tricks. I recently wrote about my family's wartime experience, and was relying on my memory of conversations had over thirty years ago with long dead relatives. It seems likely that at least some of the story I ended up conveying what mental fabrication, doubly unreliable through the fallibility of the memories of my relatives and of my own. Ultimately though, I felt this didn't matter, because the story conveyed a certain truth beyond the minutiae of the unreliable details.